How One Donated Drone Led To 40 IDF Soldiers Being Saved

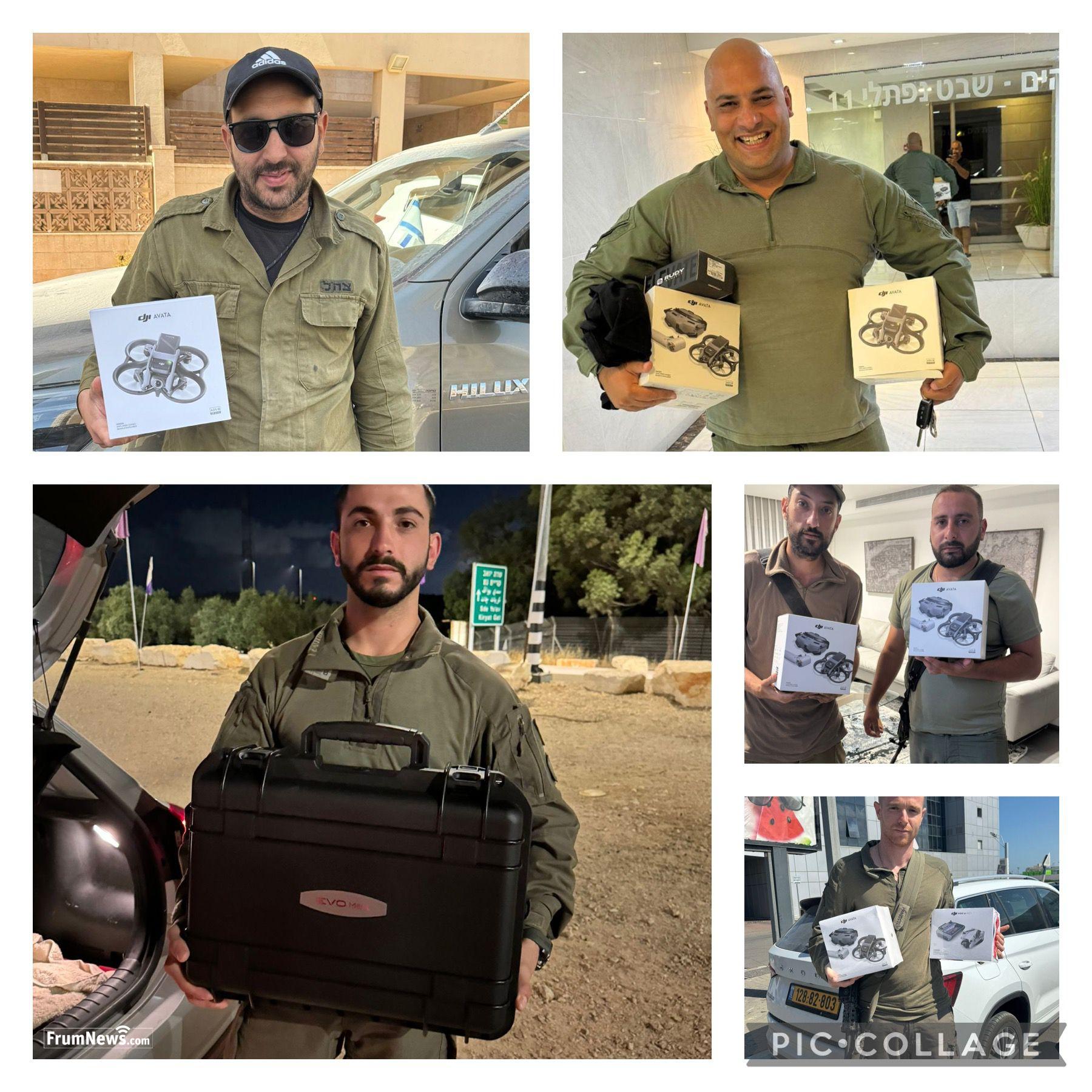

Buria Efune an independent journalist and columnist on the front lines in Eretz Yisroel shares the effect of an initiative: buying drones for soldiers in the IDF. In the following story, a drone donated to the Carmeli Reservist Brigade saved the lives of 40 IDF soldiers.

This post is by independent journalist and columnist Buria Efune. Since the war with Hamas broke out, Buria has given daily updates from the front lines in Eretz Yisroel and has helped raise hundreds of thousands of dollars for IDF soldiers stationed in Gaza through her popular ‘Updates from Israel’ WhatsApp groups and social media platform.

This article shows the effect of one of her initiatives: buying drones for soldiers in the IDF. In the following story, a drone donated to the IDF Carmeli Reserve Brigade saved the lives of 40 reservist Israeli soldiers in Gaza, B’chasdei Hashem.

-I-

40 Soldiers, 40 Brothers

I don’t think we’ll ever grow tired of getting WhatsApp messages from IDF commanders with the news that the helmets, cameras, drones, or other gear we bought saved a soldier’s life or helped locate terrorists—but the message my husband and I received after Shabbat last week was different.

It was forty soldiers.

But when we talk about forty soldiers, it’s not just forty men in uniform marching to orders. It’s not either forty heroes battling an enemy so that we can sleep at night, safely in our beds. It’s forty brothers in our tiny family.

Two weeks earlier, my husband brought a special fireproof Tefillin case to the younger brother of his close childhood friend. Dov Igbi is the little brother of the type of friend who twenty years later, and a few continents over, still calls every few weeks to catch up, and still shares secrets and concerns, heart to heart.

Dov is in the IDF reserves, and his unit was being transferred to fight Hamas in the center of Gaza. He makes sure to pray with his Tefillin every day, and wanted a special case to ensure that the fragile texts don’t get ruined between the heavy fire.

There’s always an awe and pride in our soldiers, along with a concern and worry that we try to shove down to the bottom of our throats. My husband wished him the best, and that G-d watch over him, before seeing him go off to Gaza.

The message we received a few days later was from Dov’s commander. He was exuberant, perhaps in a mixture of shock and gratitude to be standing at all. His unit had just arrived at a mission point in Gaza, and were setting up base in an abandoned building. Forty soldiers spread out on two floors and got to work covering up windows, and drilling sniper holes.

The unit scout took out the drone and began to search the extended area, taking an extra close look in and around buildings in the distance. We had purchased the drone with extra funds from donations from my readers, and sent it to the unit a few days earlier. It was a budget drone—the Mini Pro 4–but it did the job.

After a minute of searching, the soldier spotted a Hamas terrorist with an anti-tank missile aimed directly at the building where forty soldiers were settling in. He was close enough that the hit would be certain disaster.

The scout immediately called to the team sniper, pointed the position, and eliminated the terrorist. They then called in an air strike to remove the missile and launcher. The drone saved them.

Forty soldiers. One was Dov, but all of them were brothers.

A few days later, half of the unit was out on a break, in a base nearby. My husband and I, and Alice, who is our team drone expert, went to see how they were doing, and learn more about the use of drones in battle.

It was a makeshift army base for reserve units. Past the improvised security gates were rows of large sandy tents, lined with military cots that looked less comfortable than a bed of nails. In the back of one tent stood a fridge with a glass door, revealing rows of chocolate pudding and soft drinks.

The company commander invited us to sit around a small table with a group of reservists from a squad of 20, and hear their first-hand experiences.

One of them looked familiar. He introduced himself as Naftali, and I instantly knew it. “Naftali Isaacs! Your father was my fourth grade teacher in Vancouver, Canada, 20 years ago! You were in my older brother’s class!”

Naftali is the squad’s communications commander. He wears a vest laden with supplies and radio equipment that weighs at least 100lbs all together. In civilian life he’s a budding chef with an Instagram page that’ll make anyone hungry. He’s also the most vocal of the group.

Across from him sat the squad commander, who they all jokingly referred to as their rabbi. Rabbi Amit Listentover is the assistant principal of a large religious boys school in Jerusalem, and is the father of six kids. He’s exempt from reserve duty, but showed up anyway, for all five months that his unit was called for. He feels a responsibility towards his unit, who learned to look up to him as the commander over their many years of reserve duty together.

“It’s not easy,” he confessed. “My wife is struggling on her own, and my kids send me messages every day asking me to come home. My school is missing so many teachers, and I’m supposed to be arranging the classes for next year.”

He played a voice message from his four-year-old, “Abba, come home today, please. I miss you Abba.”

Next to Amit sat Tzvika, whose wife is seven months pregnant with their first child, and made him promise to come home before her ninth month so that he doesn’t miss the birth. Noam, on the other side of the table, told him that he can’t miss it for anything. Noam’s wife gave birth just before the war broke out, and now he’s missing all of his daughter’s first milestones: first laugh, first real food, first time crawling. He hopes to at least be home for her first steps. Pinchas chimed in to remind them how lucky their families are; they at least have relatives to help and support them. He is an immigrant from France, and his wife is home alone with four kids and no help.

While everyone discussed their families, Assah pulled out his laptop—he’s a computer science student, but hasn’t been able to go to class. He now studies virtually, in between battles.

The group started the war off in the north, where they guarded the border with Lebanon, and was recently moved to Central Gaza where they carry out missions along the Netzarim Corridor. Gaza has been a very different experience.

“Hamas embedded themselves so deeply in Gaza,” Noam explained. “Yesterday, a man came up to us with an elderly woman. She was crying that she’s thirsty, and walked with a limp. The man told us that he needs to take her into the humanitarian zone, and we need to let him cross the corridor with her. It was very pitiful. But then we checked the face recognition system, and found that he was a Hamas commander. It’s the same thing again and again; a few days earlier it was another terrorist, but with a group of small children and no mother. We had to take the kids over ourselves.”

Noam is considered the group leftist. They have political discussions often, especially when they were in the north on guard duty. “We argue about politics plenty,” Naftali says, “but like brothers. After a heated debate, we laugh and move on, no grudges held.”

Noam and Amit had made a bet, back when they were in the north. Noam thought the government would give in, and there wouldn’t be a Rafah operation. Amit bet them they would. A deal was made: If the IDF entered Rafah, Noam would put on tefillin every day for a month. If not, Amit would have to donate a thousand shekel to B’tselem, a far-left organization. Amit felt the risk was worth seeing Noam in tefillin.

The brotherly-bond goes far deeper than bets and light-hearted debate. Naftali pointed to two younger reservists who sat quietly on the other side of the tent. “We worry about them a lot.”

Ben and Or are the youngest of the group. They had just completed their mandatory service at the Nachal Oz outpost a month before the war began. On October 7th they lost 18 friends who they had served with, including three who were close childhood friends.

“Everywhere we go,” Assah said, “we make a memorial for all the friends we lost during the war. We weren’t able to go to any of their funerals, but we can’t forget them.”

Some of the more senior reservists said that they see therapists to deal with the pain, but wish that more of the younger ones did. “They will when they’re ready,” Naftali said. “We just need to keep supporting them until they get there.”

This brought us back to discussing the drones. Naftali got straight to the point. “It’s either a drone, or a soldier. We have to inspect almost every single building. If there’s a trap, say armed terrorists waiting behind the door, or a bomb ready to go off—who do you want going in first? A drone, or one of us?”

I looked around the table, they were all nodding solemnly. Tzvika continued, “We lost three drones since the beginning of the war. Each drone was worth 7,000 shekel and was destroyed in a booby-trapped building. But if one of us had gone in first instead of the drone, we would have been in its place.”

That was blunt. I looked at Tzvika and imagined his pregnant wife, waiting for him at home.

The soldiers had only been in Gaza for a couple weeks, but already had dozens of drone stories. A drone searching an alley found an ambush waiting for them, a drone searching a building found traps, and another found a terrorist jumping into a tunnel. They also had stories with no drones.

“Last week my friend, who is a sniper, got hit by an RPG and was seriously injured,” Naftali said. “His unit doesn’t have a drone. I’m sure they would have found the terrorist if they did, and my friend wouldn’t be in the ICU.”

Drones funded by civilians have slowly been filling up the battlefield, and changing the rules on ground. The soldiers are certain that the daily IDF death-toll dropped significantly because of the drones.

A simple drone costs 7,000 shekel, and a more advanced drone with night vision costs up of 22,000 shekel. The IDF bought a very limited number for a few elite units, but not for every unit and squad, which the combat commanders are all saying is necessary. While the reason isn’t known for sure, there is speculation. Most drones are made in China. Other drones are made in the U.S., where the IDF has a military trade agreement. Some speculate that the Biden administration doesn’t want the IDF using drones, since it leads to more buildings being destroyed by airstrikes, instead of the terrorists being eliminated in gun battles.

“Listen,” Amit said. “We’re here to fight for our nation’s survival. We left our families for half a year so that they can live a whole life in security. I don’t want my kids or students to have to fight or mourn a single day like we do. We will do whatever we need to, with whatever we have.”

We sat around talking for two hours, my husband, Alice, and I, listening to their stories. A group of soldiers turned into a group of brothers. Each who need to return to their loved ones whole; and in our hands the power to do something to help make that happen.

-II-

Ben and Or’s story

We were getting ready to leave the base when Naftali suggested I meet Or and Ben.

The two sat together on a cot in a corner of the huge tent, their military vests and guns dropped to the side. They looked at least ten years younger than the other reservists we had spoken to. They also looked heartbroken.

“They finished mandatory service just a month before the war began,” Naftali explained. “They were assigned to our team for reserve duty, and met us for the first time on October 7th.”

The team are part of the Carmeli Brigade, which is made up of reservists from the Golani Brigade. After doing mandatory service, soldiers get assigned a reserve unit, usually with some friends from their original squad. From then on, they meet up with the same group once or twice a year, or whenever there is a war. Over time, reserve squads of 20 develop a close bond and care for each other like brothers.

On October 7th, the Carmeli Brigade was sent to guard the northern border, then after six months they were moved to Central Gaza.

Ben and Or invited us to sit down on the cot parallel to theirs. I felt out of place, in my civilian clothing, coming from my everyday life, sitting in between piles of dark army green gear, on a stiff bed amidst the rows that lined the tent. But the two looked like they could be my younger brothers; Ben with his curly hair and tidy beard, cooling down in his military tzitzit, and Or with his Mizrachi skin tone and jet black hair—flip flops on his feet in place of the heavy boots he wore all day. Both with piercing eyes that gave away experience far beyond their age.

Ben started, “We served at the Nachal Oz outpost for two years. Our job was to guard the border. It was the army, but we had good times.”

At night they’d sit around and sing, make lighthearted jokes at each other, and share good food they got from family—or fire up a can of tuna if they had none. They were proud to wear their uniform, and proud to be in Golani.

“When the new recruits came in,” he continued, “we showed them around, and took them under our wings like we do in Golani.”

Naftali jumped in to explain. “In Golani, it’s the job of older soldiers to pass down the Golani lore to the next generation. We always say—we might not be the brightest bunch, but we’re the ones you call when you need to get the job done. We don’t give up for anything. The younger soldiers need to know that’s who we are.

“I’ll give you an example from just two days ago: My team sniper got his finger blown off. He went with another guy to the hospital to get it stitched back together, and asked the doctor to hurry, because he had to get back to us in Gaza. The doctor looked at him like he was crazy, and then said, ‘Oh, you must be a Golani.’ Everyone knows it about us.

“That’s why October 7th was so hard for Ben and Or. It was their friends, but also the kids they trained to be Golani. And they felt like they abandoned them.”

Or looked down, his eyes seemed to be seeing something far away. “The first thing we heard that morning was that one of our friends was killed. But the messages were coming in slowly, and very unclear. We wanted to rush down and help them, we felt like we were supposed to be there with them—we would have been if it was only a month earlier!”

“We debated it,” Ben continued. “We knew we were supposed to join our new reserve group on the northern border, and that’s where we would be given our gear. But our friends were fighting for their lives down at Nachal Oz. We almost went empty handed. We figured we’d either find a gun somewhere, or we’d fight with our fists. At least we would have been there with them. Maybe we could have saved one of them.”

Or pulled out a large sticker with a photo of a smiling young soldier. “Dolev Amouyal was our machine gunner. He was 21-years-old, a big guy, not just physically, but in personality too. He was a leader, everyone always looked up to him to know what to do.

“He was on patrol that morning with one other guy, and quickly rushed up to help, firing at terrorists while speeding to the base. A rocket landed directly on his Jeep, splitting it in half. The other guy lost his arm, and Dolev was instantly killed.”

Ben and Or made stickers in memory of Dolev, and developed the habit of sticking them wherever they fight—on the Lebanon border and in Gaza. They feel it keeps him alive, and also avenges his death.

“Sometimes I don’t know what to do,” Ben spoke slowly. “You know, things get tough out there, and I could use good advice. It feels natural to call Dolev—it’s what I’d always have done. Then I reach into my bag and all I have is these stickers.”

I didn’t know if I should let them see the tears welling up in my eyes, or hold them back because they had enough of their own.

“We lost eighteen friends that day,” Or said. “I didn’t think Daniel could ever die. We called him by his last name, Danino. Danino could make a rock laugh. He was hilarious, and no one was immune. But he wasn’t just funny; he was a genuinely happy person. From the day he was born.”

“He could sniff sadness too,” Ben took over. “If someone was having a hard time, he’d go over, and show that he really cared. He looked out for everyone, like he had a radar or something. But he was a real Golani until the end.”

On the morning of October 7th, Danino found himself on the frontlines at the Erez Crossing, fighting against a swarm of Hamas’s elite Nukhba terrorists. He directed a group of unarmed female soldiers into a building, and together with four other soldiers, guarded them until his last breaths.

“He saved them,” Ben said simply. “He was always like that, thinking about everyone else first.”

There was a long pause. I didn’t want to push it.

“But we were in the north, far away from all of them,” Or trailed off.

“You know it’s not your fault, right?” I asked. “You also saved people by guarding the northern border. You also risked your life every day. We all know that.”

Ben shook his head, like I didn’t know what I was talking about. “We didn’t get to go to any of their funerals. We didn’t say goodbye.”

“We had to act like nothing happened,” Or filled in. “There was no closure, nothing to make reality hit. Just sitting in trenches in the far away mountains. Wondering if we made the right choice that day.

“After five months, we had three weeks off,” Or sat up. “We visited all of our friend’s families. We did what we should have done the week after they died. We sat with their parents, Dolev’s, Danino’s, Yaron’s, all of them, and told them all about their hero sons.”

“That must have been exhausting,” I commented. “But so brave.”

Again, Ben shook his head. “Their parents were so happy to hear all the stories of the good times. We laughed together and cried together, and hugged. It was like they were our family and we were theirs. We’re the only people who understand each other, the only ones who know what the world is missing.”

The two visited eighteen families in three weeks. Not to fill the screaming hole in their hearts, but to share it with the people who had the same hollow well.

Or handed me a sticker of Dolev, and stood up, “put it somewhere that matters,” I hadn’t noticed what was going on around us. The other soldiers in the tent were putting on their shoes and vests. They were being called for another mission in Gaza.

I held the sticker in my hands, and Ben nodded towards it. “We’ll always be Golani. But now we do it for them.”

***

Since the beginning of the war, the Efune family of Be’er Sheva purchased over 140 drones with the assistance and donations from dear readers and other friends around the world. We’re now at a critical moment in the war, and have urgent requests from IDF company commanders for 85 drones. After Gaza, the drones will be used in Lebanon if a wider war starts with Hezbollah. Each drone is estimated to save the life of at least one IDF soldier, but usually more.

Two weeks ago, 40 IDF soldiers lives were saved in one go, B’chasdei Hashem. Let’s save hundreds more. The goal is ambitious, but we’re a strong team—we can do it!

Click Here to donate to this Drone campaign.

Read Next trending_flat

Eretz Yisroel

Eretz Yisroel

Yeshivah Bill: Why Can't Our Bochurim Just Learn Torah?

Exclusive

Exclusive

Shai Graucher’s Movement of NON-STOP Chessed

Eretz Yisroel

Eretz Yisroel

Post the first comment!